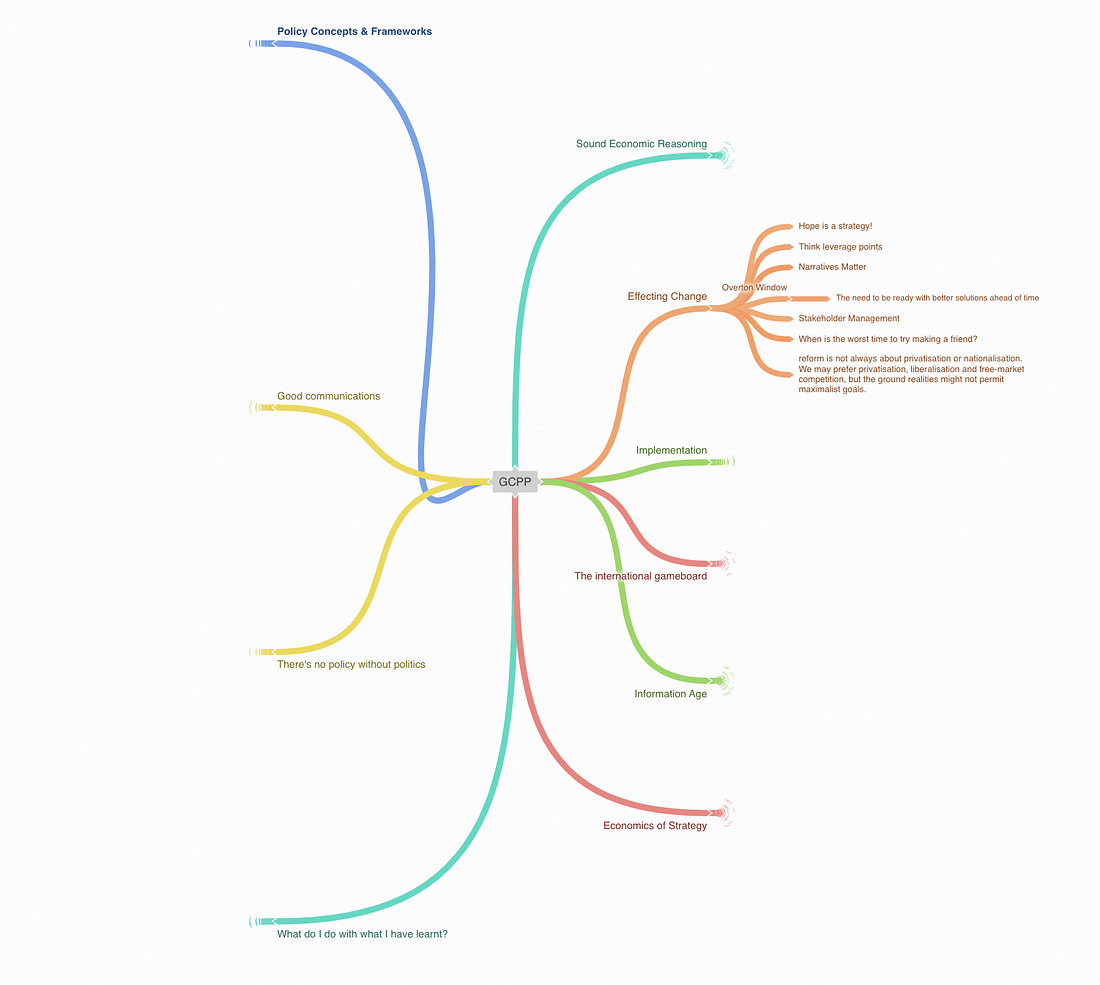

Course Advertisement: Here’s a mind map preview of ideas students learn by the end of the 12-week Takshashila Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (GCPP) programme. Intake for the 41st cohort closes on April 20. Apply and tell your friends. You’ll find all the details here.Global Policy Watch: DisorderInsights on global issues relevant to India— RSJIt is difficult to write on any other topic in a week when Trump made a bid to demolish the global trading order. Armed with a chart of arbitrary numbers that made no sense, on the so-called ‘liberation day’, Trump exceeded the most optimistic expectations of tariff lunatics that seem to be advising his administration. The market reaction was swift as US stocks lost more than $5 trillion in the past two days of trading as the sum total of all recession and inflation fears loomed large. It isn't easy to take anything seriously from this administration. For instance, the reciprocal tariff formula for different countries wasn’t based on the actual weighted average tariff on goods. Instead, it appeared to be the ratio of a country's trade surplus with the US to its total exports to the US. This ratio was then halved to arrive at the discounted tariff rate to be imposed on that country. Why halved, you may ask? A White House aide said that’s because “the president is lenient and he wants to be kind to the world”. That’s right. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) confirmed this approach with a formula with a bunch of random meaningless Greek constants meant to bamboozle the average MAGA supporter into believing the logic behind this move. There was no logic. It seemed like a cram job by a bunch of interns the night before or, worse, as some have shown, possibly a response from ChatGPT or Grok. More importantly, the USTR, on its site, laid out the underlying assumption that went into the formula:

If you were to take this seriously, the only solution to getting out of these outrageous tariffs that Trump has imposed is for a country to work on reaching a bilateral trade deficit to zero. Nothing else will work, going by this. Even if a country brings its tariff down to zero but ends up running a trade surplus with the US, it will still have a stiff tariff to deal with while exporting to it. On the other hand, a country could get away with a reasonably high tariff rate if its trade deficit is zero with the US, which makes mockery of the core idea of a tariff war. In fact, such anomalies abound in the chart put up by Trump. So, Brazil gets only a 10 per cent tariff while it has some of the highest trade barriers, while EU goods will face a 20 per cent tariff with much freer trade policy. That apart, Trump hasn’t taken services into account at all in determining the trade deficit. The US is a services export behemoth, and I’m sure that in a full-fledged trade war, the world will hit back with tariffs on them. This is wrong on so many levels that it is difficult to know where to start. In any case, it is difficult to take anything seriously from an administration that is hellbent on destroying the economy and the sovereignty of Canada, its long-time ally and neighbour, while exempting Russia and North Korea from its tariff ire. Also, no one knows how such tariffs will return manufacturing jobs to the US. I don’t see companies queuing up to start factories in the US. Why would they? Will anyone want to make a long-term capex commitment based on Trump’s track record of keeping his promises? Besides, where is the labour availability in possibly the tightest job market in many years? That will become worse with deportation and stricter immigration control. Who will work in a textile or steel plant even if a company were to make that investment? And how long will all the Trump supporters hold out when inflation and recession hit them over the next few quarters? Even if the economic rationale for tariffs were sound (and they can never be that), show me an average voter with the patience to see out the tough times in the short run for some promised golden age a generation away. The consequences of this action will be seen over the next couple of quarters. China has already responded with a 34 per cent duty on all US imports apart from restricting exports of a host of rare minerals. The EU is contemplating applying tariffs on US software exports, including social media and AI platforms. There will be more from the EU, given everything Vance and company have done or spoken about the EU so far. This is something they have been looking to do, and Trump has served it on a platter. In the immediate term, this will mean a global slowdown of trade leading to a growth slowdown all over. Eventually, less trade with the US will mean one of two things. Either more autarkical moves by countries and dismantling of all WTO norms or the rest of the world will find ways to do more trade with each other with China as its engine room. No one knows how Trump will respond to retaliation from China and the EU. He might escalate the tariffs further, and that will mean pure chaos. We will be in meltdown zone thereafter. For India, there isn’t much to do immediately. A lot is being made about the opportunity India has because Vietnam, Bangladesh and most of South Asia have higher tariffs imposed on them. That would mean that in areas like textiles and low-end manufacturing, Indian exporters can be competitive if they can scale fast and offer themselves as substitutes for the US market. However, this argument overlooks the most fundamental assumption that has driven the Trump formula. If India starts exporting more, it will increase its trade surplus with the US, and that means the tariff rate will go up next year based on this increased surplus in the formula. India’s best course is to work out a bilateral deal with all kinds of exemptions to the list on which this tariff will be imposed and keep it under the radar. Any concession given to the US will be asked for by other trading partners, too. So, this will be a tightrope walk, and India will have to manage its primary bargaining chip of access to its large market judiciously. However, all of this is predicated on taking Trump and his tariff chart seriously. Despite a fair amount of evidence out there that trade balance and tariff are things that he truly believes in, and he won’t back away, I remain in the camp that like everything else, he just loves the chaos that this has unleashed. He is looking for countries to come to him to strike a deal on his terms to free themselves from this. I have no idea how many such deals he will be able to do in a short time. It takes years to close out a mutually agreeable FTA, for instance. I suspect many of these deals will be about getting concessions to help his donors, friends and family and nothing more. Basically, grift and graft. Eventually, it will fizzle out over the next year, with most countries figuring out ways to get around these rates through such deals. Trump will proclaim victory anyway, and we will return to normal times. It might turn out to be the start of a bloody trade war and collapse of the global capital and economic order. Or, it might just be a farce. With that kind of a range of outcomes, there’s not a lot we will achieve by applying our minds and thinking through scenarios. It is a Dada Kondke movie that’s playing. You won’t get much analysing it as a Satyajit Ray work. Addendum—Pranay KotasthaneAs RSJ writes, analysing the logic behind Trump’s tariff formula has diminishing marginal utility. At least they released the document explaining the flawed reasoning behind the new tariff regime. I don’t remember our government telling us the logic behind India’s high and arbitrary tariff regime, nor has it cared to explain the need that led to the horrendous Chip Import Monitoring System (CHIMS). Given the tariffs as they are, what should India’s stance be going forward? Four broad options are possible. The first is to do nothing, which in this context means continuing with the status quo. This option means no retaliatory tariffs on the US and focusing on getting the Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) through later in the year, as was the plan before April 2. The former commerce minister Anand Sharma seems to represent this view in his Indian Express article:

The second option would be to confront the bully. This could mean applying retaliatory tariffs on American goods, stopping the purchase of its petroleum products, and calling off some of the terms agreed during the last prime ministerial visit. Pratap Bhanu Mehta seems to be of this view. From his hard-hitting Indian Express column:

The third option would be to engage in rhetoric. This could mean applying retaliatory tariffs to many goods that America doesn’t supply to India in meaningful quantities, just to make a point that India won’t take kindly to a further escalation. A fourth option would be to drastically change incentives. This could mean a transition to a low-tariff regime not just for the US but for all countries in the world, signalling that while the world may be closing, India is open for business and trade. Another variant of this option might retain anti-dumping or countervailing duties on China, given its unfair practices that produce structural overcapacity. Shoumitro Chatterjee is of this view. From his Indian Express article:

Of these four options, the last seems most desirable, but the first (do nothing) is most likely to play out for now. The option of confronting the bully, though principled, is an avoidable escalation. India should lie low while the US and China exchange barbs. India’s weak position in the global trade of goods means the only way to make retaliation work is by joining hands with other countries. This is highly risky because it’s a Prisoner’s Dilemma situation—countries will defect from the coalition and bandwagon with the US as soon as they get any concessions. The same problem applies to the option of engaging in rhetoric. Though it might not have any real effect in terms of trade, it will signal an escalation and take the heat off China. The fourth option seems to be the most pragmatic course of action. Before April 2, I thought the momentum was building towards this option. Government ministers were suddenly speaking about the evils of protectionism and exhorting domestic firms to pull their socks up. However, I fear the Overton Window has closed after April 2 for such a response because of two narratives. First, India's relatively low rate of Trump tariffs compared to other Asian competitors makes status quoists think they have done enough already. And two, a tariff punishment despite India's preemptive moves promising reduction in tariffs for some US goods might strengthen status quoists who will say, "let's wait it out, why let Trump set the pace?" With urgency out of the way, status quo always wins in large institutions. So, the chances of a significant trade reform remain remote. This leaves the first option (do nothing) on the table. India’s inclusion in the tariff list would’ve weakened the position of this plan’s proponents. The PM’s trip to the US now doesn’t have anything to show, pending the outcomes of the BTA negotiation. However, it is politically easier as a limited BTA with the US is less likely to ruffle feathers than a major trade reform. So here we are. Trump’s tariff threats first created a familiar Indian policy narrative—let’s turn the crisis into an opportunity. Without any firm conviction about the reform idea, the moment zoomed past us. So we will wait for another crisis and then rue another missed opportunity. Call it the Niti kaalchakra. India Policy Watch #1: A Ray of HopeInsights on current policy issues in India—Pranay KotasthaneThis newsletter has consistently advocated paradiplomacy. Indian states are not only domestic actors but also geopolitical and geoeconomic entities. In edition #171, we wrote that Indian state governments should follow Australia’s example by having permanent trade and investment desks in important world business centres. We wrote:

Given this view, N Madhavan's excellent Mint report on Tamil Nadu’s non-leather footwear industry made for pleasant reading. The report says Tamil Nadu has attracted major footwear brands like Nike, Crocs, Puma and Adidas to set up manufacturing facilities in the state. As is the case with semiconductors, even non-leather footwear is contract-manufactured. And as with semiconductors again, the big contract footwear manufacturers are Taiwanese names we would have never heard of! The part of the report that excited me most was that Tamil Nadu’s economic diplomacy played a key role. Here’s how:

So it seems Tamil Nadu is first off the block on this count. It should go one step further and have a permanent trade and investment desk in other manufacturing centres of the world. The Union government should formalise this template so that other states can realise their potential as geoeconomic actors. India Policy Watch #2: Do Your DharmaInsights on current policy issues in India—Pranay KotasthaneI guess enough people have panned the Commerce Minister’s critique of India’s start-up ecosystem at a government event meant to encourage start-ups. I agree with the view that it’s not the government’s business to give product-market fit gyaan. While much of the blowback has focused on the policy impediments that start-ups face, the root cause lies elsewhere. With our governments failing to do the things only governments can do, much of the well-meaning affluent India is busy trying to substitute governmental failures. And so you have every major charitable trust solving for India’s poor primary education while every other start-up is delivering things to our homes because walking on our streets is a risky, unpleasant experience. These failures redirect society’s ambition and efforts from excellence and global competition to creating India-specific hacks. Nevertheless, this debate indicates that India is facing what Mark Zachary Taylor calls “creative insecurity” in his book, The Politics of Innovation. The idea is that only when nations feel ‘creatively insecure’ due to external challenges do national policies focus on innovation more than before. For too long, we were content with being the leading economy in the sub-continent or a partner to the West. Only the emergence of a technologically superior China as an immediate geopolitical threat has moved the needle on innovation policies. There is much more discussion inside and outside the government on climbing the innovation ladder. And the hope is this manthan will lead the government and businesses to prioritise research and product development. P.S.: The minister’s criticism felt like the Indian ODI bowling team of the 1990s—after conceding 350+ runs—publicly criticising Sachin Tendulkar for not scoring a century in the chase. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

|