Insights on global issues relevant to India

— RSJ

Good to be back after three weeks. We were expecting a quiet, short break with the usual news cycle of the US elections with Harris in the lead, the wars in Ukraine and Lebanon, and the predicted Congress win in Haryana raising the domestic political temperature. Instead, what we got was a bizarre India-Canada diplomatic face-off, Israel wiping out much of Hezbollah's top leadership and trading rocket fire with Iran, an unprecedented month-long FII sell-off in Indian markets with hot money moving to China on the back of its stimulus, and a surprising win for BJP in Haryana followed by a political assassination in Mumbai and the seemingly all-pervasive presence of the Lawrence Bishnoi gang. There’s a lot to catch up on.

India and Canada are on a path of complete diplomatic breakdown in a month where Canada levelled fresh allegations about India carrying out criminal activities on its soil with the active involvement of the local embassy staff. The two countries expelled their top diplomatic staff in a tit-for-tat response, with India accusing the Canadian PM of pandering to local extremist Sikh factions for electoral gains. India actually used the term “vote-bank politics” in our official communication, which is a terrific term that we should proudly export.

From everything that we have read and heard from Canada and the concurrent investigation that’s on in the US about a foiled assassination-for-hire plot against Khalistani extremist Pannun, it will be difficult for India to dismiss all of this as a figment of Trudeau’s imagination. I suspect there will be more evidence that will pile up about the involvement of Indian actors, and our playbook will be to deny any link to the Indian state. It will be a difficult diplomatic tightrope to manage, and beyond a point, we will just have to brazen our way out using whatever ‘swing power’ leverage we might have.

What I still cannot appreciate is how much of a real threat are a bunch of Khalistanis sitting in Canada to our sovereignty. Is there a real movement for a separate Sikh nation among the youth in Punjab like it was back in the 80s? I don’t imagine Pakistan is in any position now, unlike back then, to foment any kind of unrest. So, what’s the nature of the risk that could have prompted India to try out a political murder on the soil of a friendly country? Canadian political parties might be pandering to fringe Sikh elements for electoral gains, and some of these radicals are engaged in anti-India rhetoric to boost their popularity, but that’s been going on for a while. Someone likely got carried away trying to showcase counter-terrorism capabilities in the run-up to the last Lok Sabha elections to burnish the muscular nationalism appeal (the old ghar mein ghus ke maara). Whatever the reason, this will get messier before it sorts itself out. And it will require a fair bit of ‘give’ for India to save face and get out of this eventually.

China’s massive stimulus announced late in September meant a massive selloff by FIIs in the first three weeks of October. So, is the stimulus beginning to work for China? As I mentioned before, there are three key policy objectives for China right now - a) stay the course for 5 per cent GDP growth for 2024; b) derisk the economy from high local government debt and a housing market bust; and c) boost domestic demand and consumption.

Nothing in the last month suggests a sustainable shift in direction towards meeting these objectives from the stimulus. GDP growth for Q3 came in at 4.6 per cent. The housing market stabilised somewhat, with new house sales falling by 11 per cent y-o-y since the stimulus was announced from the earlier 20+ fall. Some more measures were taken in October by the Housing ministry, but these don’t look sustainable, as has been the case with multiple such announcements in the last 12 months. Eventually, until the government announces clearly that it will act as a buyer of last resort, China won’t get out of its housing crisis for good.

Even the stock market upswing of the last month to me looks temporary. Global growth is looking more shaky now, and with the continued protectionary measures and trade tariffs being raised all around, it doesn’t look like China will see any export boost any time soon. The recent stimulus won’t address the long-term structural issues of high savings, high government debt and over-reliance on investment-led growth. Much of the FII move to China is a short-term trade, and traders will book profits and move out before the end of the year.

In the meantime, China is beginning to look more like Japan with what the Financial Times calls a “lot of eerie parallels”. Here’s one specific example from the FT:

“Yep, the 30-year government bond yields of China and Japan are on the cusp of crossing paths for the first time (ever, we think, but LSEG data for both 30-year benchmarks doesn’t go further back than 2009).

At pixel time there’s still a 10 basis point spread between the two long-term bond yields, with the Chinese 30-year yielding 2.245 and the Japanese 30s trading at 2.144 per cent. But it looks like that won’t last long. Shorting Chinese government bonds really has been the new widow-maker trade.

The fading yield curve differential is another stark manifestation of China’s growing economic and demographic malaise, and Japan’s (for now) success in finally winning a three-decade battle against deflation…

Here’s what Barclays’ economists said in a big report on the topic last month:

“The economic circumstances facing China have parallels with Japan’s experience after its asset bubble burst in the early 1990s. This created the term ‘Japanification’, which is typically defined as a combination of slow growth, low inflation, and a low policy rate, accompanied by deteriorating demographic trends.

To measure this phenomena, a Japanese economist, Takatoshi Ito, introduced a Japanification Index, which measured the sum of the inflation rate, nominal policy rate, and GDP gap. To apply to China’s economy, we have adjusted this index, replacing the GDP gap with working-age population growth, as the estimation methods of GDP gaps differ across nations and working-age population is by far the most fundamental determinant for long-term growth. Our amended index shows that China’s economy has become more ‘Japanised’ than Japan’s recently, albeit marginally.

This is not a surprise to us. A demographic drag, the emergence and collapse of asset bubbles, debt overhang, zombie companies, deflationary pressures from excess capacity/high debt, and high youth unemployment, to name a few, are some of the notable similarities between the economies of China and Japan post their bubbles.”

Lastly, the Haryana election results shocked every single pollster and political analyst. It is difficult to understand how every exit poll got this so wrong in a small state where there was a direct fight between the BJP and Congress. I haven’t seen any analysis from the analysts on what went wrong - sampling, seat conversion, preference falsification, or whatever else. The Maharashtra elections set for later in November will have 6 parties in two broad coalitions and that will be almost impossible to predict. I will be interested in seeing how the pollsters approach the opinion and exit polls there. These are strange times for them. And for the voters.

Insights on current policy issues in India

— Pranay Kotasthane

N Chandrababu Naidu and MK Stalin were in the news for their comments on declining fertility rates in their respective states. At this stage, these comments don’t amount to significant policy change. These could well be starting positions of state governments that foresee a reduction in their relative power after the upcoming Lok Sabha seat apportionment exercise (colloquially and inaccurately referred to as Delimitation). Nevertheless, these comments are worth considering, given how quickly “population” springs up in any debate on Indian policy, politics, and collective behaviour. Here are my four observations.

One, the Indian debate ties into a global conversation on declining fertility rates. A recent article in the Financial Times by John Burn-Murdoch explains that authoritative population projections have been underestimating the decline in total fertility rates worldwide. It is not just a rich-world issue; developing countries have caught on to the trend faster than expected (thanks to the upward shift in the Preston Curve). For instance, Mexico’s reported birth rate this year is already lower than that of the US. Fertility rates across West Asia, Latin America, and North Africa have also fallen faster than what the projections accounted for. The article suggests that if we were to extrapolate the actual birth rate declines, the global population would peak at around 9 billion in 2054, a full three decades ahead of what current projections suggest.

These are not just statistical artefacts. These developments will also impact economic growth. It is possible that people in developing countries might become older and fewer before they become richer. A recent NBER working paper by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde et al. suggests that a larger working-age population is a major determinant of economic growth. They find that Japan’s lacklustre economic growth isn’t an outcome of lower productivity or poor monetary and fiscal policies but simply because of its declining working-age population. Japan's productivity per worker has remained relatively stable and comparable to that of the US, suggesting that Japan's economic challenges stem not from a lack of innovation but from a shortage of workers to drive production and consumption. Thus, there seems to be some merit in thinking through the consequences of these trends.

Two, governments worldwide have tried various policies to reverse the declining fertility trend but haven’t succeeded. Once a demographic change is set into motion, there is an inertia that defeats the force of government policies. The Soviet Union instituted a Mother Heroine title in 1944, awarded to women for bearing and raising a large family. Nevertheless, fertility rates kept declining. In any case, Putin revived this title in 2022, hoping for better luck this time around. Serious governments have tried funding childcare and modified parental leave policies but haven’t been able to make a big dent either. If governments of richer countries haven’t been able to move the needle despite policies and programmes to finance raising children, it is unlikely that vague exhortations by Indian politicians will turn the tide.

Third, an exhortation to have more children won’t serve the instrumental purpose of addressing the perceived imbalance in political and economic representation. For we know that policies relating to demographic changes—such as pensions, birth rates, and retirement age changes—are generational, multi-decade efforts. Thus, even if Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu were to start on this path, it would not impact the proximate fears they have raised about Lok Sabha seat apportionment.

Fourth, given the global experience, our governments must change their mindset about targeting a certain golden population-to-resources ratio. The desired outcome should be to generate prosperity for people who exist today rather than forcing people to have more or fewer children in the distant future.

In our book, we have a chapter titled Aabaadi Isn’t Barbaadi, in which we argue that population is a neutral variable. Population—big or small—shouldn’t be considered a problem. Rather, the focus should be on how to generate prosperity for everyone. In that context, there are multiple causes for the steep fertility rate drops, some of which are quite desirable. For example, increased female economic empowerment and autonomy and better contraception are some leading causes. These changes have crucially enabled more individuals to chase their dreams by forgoing the monetary and opportunity costs of raising children. Who is the government to question these life choices?

The government’s position should start from humility that a lower fertility rate is a revealed preference of people and that directly addressing fertility rates is unlikely to change outcomes drastically. Instead, if they really care about a declining population., they should lead the charge on reducing barriers to migration, increasing retirement ages for the elderly, and implementing family-oriented policies that reduce the parenting burden.

PS: What’s striking is that it took less than fifty years for us to move on from government-backed forced sterilisations during the Emergency to a situation where government functionaries now want to increase fertility rates. On demography matters, it’s best to be sceptical of government policies.

Leave a comment

Big fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action

— Pranay Kotasthane

Now that India and China have moved towards reducing tensions in some border areas, is it time for a grand rapprochement with the other troublesome neighbour?

We’re realists here. A similar high-level overture towards Pakistan is bound to elicit an unsavoury response from the Pakistani military-jihadi complex and hence must be avoided.

In 2016, Rohan Joshi and I wrote in Livemint:

A prevalent view in India is that sustained dialogue at the highest levels offers the only realistic chance for peace…

In reality, talks, especially at higher levels of the political ladder, have a close correlation with provocative action from Pakistan. Vajpayee’s visit to Lahore in 1999 was followed by incursions in Kargil and the attack on the Indian Parliament came close on the heels of Pervez Musharraf’s visit to Agra. This time, Modi’s surprise visit to Lahore yielded a three-pronged assault on India: first, at Pathankot air base, then at Indian consulates in Mazar-i-Sharif and Jalalabad in Afghanistan.

These provocations underscore the Pakistan army’s thinking as it relates to India and shatter the carefully constructed narrative of its commitment to the new peace initiatives. The Pakistan army has long since institutionalized hostility towards India and sees itself as contesting not only territorial space with India, but also ideological frontiers (as articulated in the Pakistan army’s 1994 Green Book). It is not what India possesses, but rather, what India is, that agitates Pakistan. Thus, for example, the popular notion that resolving Jammu and Kashmir territorially will lead to lasting peace between India and Pakistan holds no water…

It is important to recognize that the defining value of the Pakistani military-jihadi complex—a dynamic matrix of military, militant, radical Islamist and sociopolitical-economic structures—is that reconciliation with India is detrimental to its interests and survival. It explains why previous negotiations, however close they might have been to a solution, have failed; the complex strikes back whenever it feels threatened.

History also provides little evidence to support the argument that Pakistan’s civilian leaders are fundamentally committed to peace with India. To their credit, some Pakistani leaders (like Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari) have made statements in support of better relations with India. Yet, Pakistan’s two largest political parties also have an unfortunate track record of supporting and implementing policy hostile towards India.

Benazir Bhutto, for example, diplomatically internationalized Kashmir and ramped up aid to militant groups. Her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, was the chief architect of the 1965 war and of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme. Most political parties in Pakistan, like Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (N), have also historically allied with militant groups—including those inimical to India—for political gain. They will likely find that severing ties with these groups is not as easy or convenient as it might seem.

India must recognize that talking to Pakistan is no guarantee against terrorism, just as not talking to Pakistan cannot ensure India of a terror-free environment. Only by putting in place mitigation strategies can India hope to better protect itself from the terror infrastructure that continues to thrive in Pakistan. These mitigation strategies require India to muster resources at its disposal (including political, diplomatic, economic and military) and channelize them much more effectively to both insulate the country and impose costs when transgressions occur.

As for the current peace initiatives, India is better served by leaving the handling of its Pakistan policy to civil servants and diplomats, rather than its political leadership. The Modi government is better off putting grand rapprochement with Pakistan on hold while expending available political capital to launch economic reforms and get the country onto the bullet train to prosperity.

With hindsight, we can say that the Indian government’s approach has been exactly along these lines. It has treated Pakistan as an irritant rather than a challenger and invested political capital in building other partnerships of greater consequence.

Even so, we think that it makes abundant sense from a realist’s point of view to open up a technical dialogue with Pakistan on an issue that poses a bigger threat to India and Pakistan together than they do to each other: climate change.

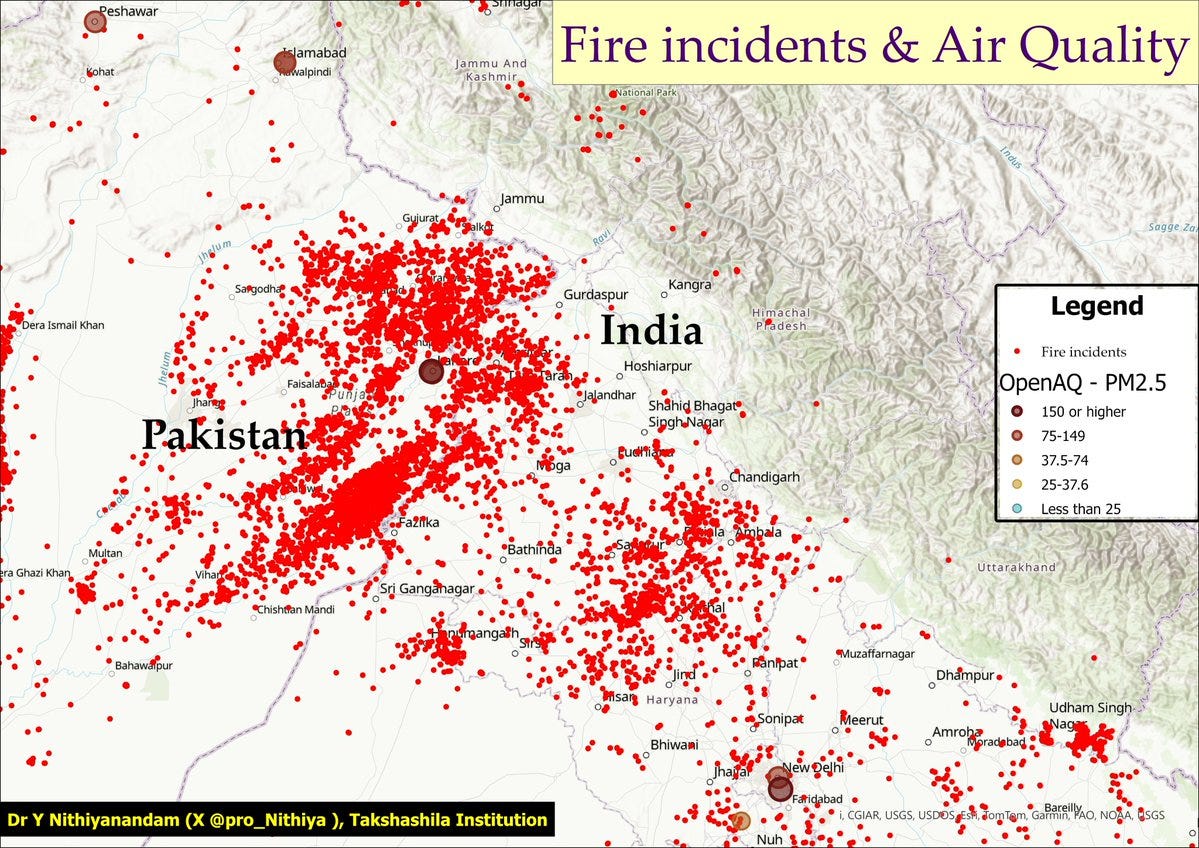

We are entering the deadly winter months, and air pollution levels in Delhi and Lahore have risen alarmingly. Even as the two countries address the domestic causes of the recurrent smog, it is clear that many affected areas are a part of the same regional air shed, meaning that what happens in India’s north-west affects the smog in Pakistan’s Punjab and vice versa. My colleague Dr Y Nithiyanandam has documented this effect here. Earlier this month, Maryam Nawaz Sharif also raised the issue of "climate diplomacy" with India to address the issue of smog.

While the focus on transboundary cooperation on air pollution is welcome, it is just one of the several environmental issues that poses a threat to both countries. In our next discussion document, titled Environmental Cooperation: An Imperative for Subcontinental Thinking, we document other issues: urban heat, glacial melt, storm surges and changing river paths. Each of them has a transboundary element—what happens in India affects the situation in Pakistan and vice versa. Thus, cooperation at some level is a necessity and not a choice. Here’s a summary:

India-Pakistan relations have been strained since the partition of the subcontinent, and efforts to overcome differences and improve bilateral relations have been largely unsuccessful. However, today, both countries face serious environmental issues, which, if not addressed, can potentially hurt them more than they can hurt each other. Climate change knows no borders, and subcontinental action is the need of the hour. India and Pakistan have young populations– India has a median age of 28 while Pakistan has a median age of 20– who will bear the brunt of environmental issues in the coming decades if urgent action is not taken.

Their shared climatic and geographical characteristics mean that India and Pakistan face many of the same issues in tandem, and climatic events in one country often affect the other. Heat waves, air pollution, rising water levels, and glacial melting are four areas that impact both countries on a large scale. They have far-reaching implications- ranging from affecting the liveability of cities and catalysing major health issues to impacting food and water security. This discussion document looks at some of these problems and explores mechanisms for them to be addressed. Through the example of the locust swarms that ravaged both countries in 2020, it explores instances where cooperation has effectively brought about changes.

We are not peaceniks. Far from it. Hence, we advise against grand prime ministerial dialogues. We instead advocate low-key technical mechanisms to tackle these issues. The ongoing cooperation through the Locust Warning Organisation (LWO) to monitor locusts and provide early warnings of their presence, which includes joint border patrols and coordinated pesticide spraying, serves as a good template for climate action cooperation.

Climate change is an issue that isn’t coloured by past betrayals, unlike other issues such as cricket, people-to-people exchanges, and trade. Moreover, it will have a significant bearing on the future generations of both countries. Given India’s power differential and Pakistan’s need for an economic revival, it makes sense from a realist lens on both sides to open a technical dialogue on climate-related issues. For all we know, it might even open up the space for discussing the more contentious issues.

For more, read this document and tell us what you think.

Reading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

[Article] Read this article on fertility rates in India by Sonalde Desai, India’s top demographer.

[Video] How Does Low Fertility Affect Economic Growth Worldwide? — This conversation between Jesús Fernández-Villaverde and Alice Evans is terrific.

[Video] Here’s our Lok Sabha Seat Apportionment Deep Dive Puliyabaazi.

[Article] BRICS is back in the news again. A quick take: BRICS formation needs China more than China needs BRICS. But Russia needs BRICS more than anyone else. This opinion piece from 2016 applies well to BRICS even today—an indication of what the group has achieved (or not) thus far.