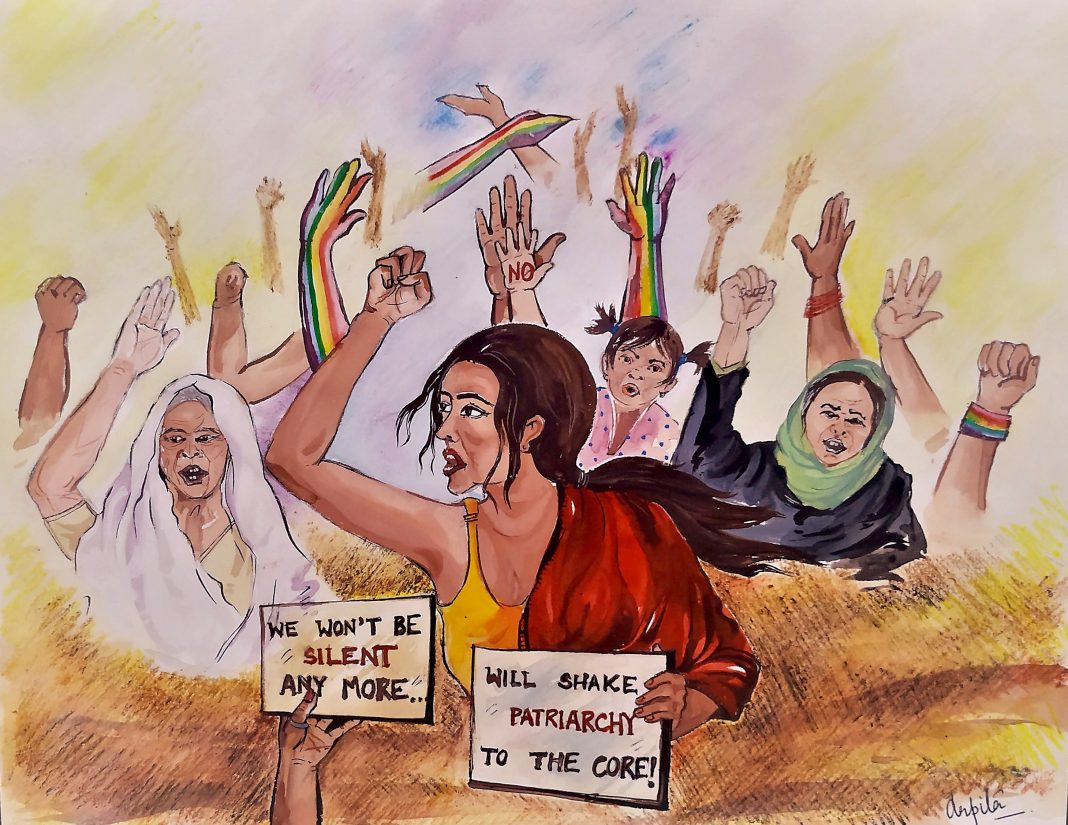

| In the public imagination, rape is a crime committed by strangers lurking in dark corners. But an overwhelming number of rapists are known to their victims—a fact the Burari rape underscores in all its sordid details. There’s a trigger warning, but if you can, read on... The Big Story Home truths: Beware the monster inside After her father died of Covid-19 in October 2020, her mother sent her to live with the family of a man she called ‘mama’ (mother’s brother). Like the girl and her mother, Premoday Khakha came from Ranchi. Both families went to the same church (not associated with any diocese) in Burari, Delhi. Moreover, Khakha occupied a position of responsibility as an assistant director in Delhi’s women and child development department. What could possibly go wrong? Reports containing details of a police complaint will make you sick. They state that between November 2020 and January 2021, Premoday Khakha repeatedly raped the girl, then aged 16. In January when she got pregnant, she told his wife Seema Rani who blamed her for the crime and then reportedly asked her 22-year-old son to go and buy abortion tablets. In February 2021, the girl returned to live with her mother, telling her she didn’t like living with the Khakhas without elaborating on reasons why. Bottling up such a traumatic experience led to anxiety attacks that only seemed to get worse. On August 7 this year, her mother took her to a hospital for treatment and it was during counselling that she spoke about the rape and abortion. A first information report (FIR) was filed at Burari police station on the evening of August 12 but strangely no arrest was made under the stringent POCSO act. Khakha and his wife were arrested only after the police finally recorded the girl’s statement on Monday and the story became public. The delay in the arrest is most “unfortunate” said Delhi Commission of Women head Swati Maliwal who sat on dharna to try to meet the girl and her mother but was denied access by the police. “There is no deterrence, no certainty of punishment and that is why the intensity, brutality and number of cases is going up.” “Policing is supposed to create a fear,” she continued. “But obviously people believe they can get away if they are in positions of power, whether it is Khakha or Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh [outgoing president of the Wrestling Federation of India].” Read: Four women had officially complained about harassment by Khakha Acquaintance rape  Protests in New Delhi following the gang rape of a 23-year-old woman in December, 2012.(File Photo) In the public imagination, rape is a crime committed by strangers lurking in dark corners. But an overwhelming number of rapists are, in fact, known to their victims. Of the 31,677 rape cases registered in 2021, 96.5% of cases, were committed by family, friends, neighbours and other known people, finds the National Crime Records Bureau. A 2015 study by Majlis Legal Centre examined rape and sexual assault FIRs filed in Mumbai between 2014 and 2015 to find that 90% were by people known to the victims, including 16% by a family member (73% of these were a father or a stepfather). Despite the data, policy around rape focuses on women’s safety in public spaces with the onus placed on women and girls to prevent getting raped either by being discouraged to go out or through self-defence classes and the like. When boys and men are engaged, it is to appeal to their better instinct as protectors of women. This allows them to “safely distance themselves from ‘men who rape’,” writes Arpan Tulsyan, a development sector researcher. But it also “reinforces the notion of male paternalism”. It also ignores the rapist at home. When the rapist is someone within the family—a stepfather or close blood relative—the family might be reluctant to report, particularly if they are financially dependent on him. “There is an attempt to underplay the enormity because in most cases, the accused is a relative, a neighbour or a person known to the child,” says Soha Mitra, director, north, CRY (Child Rights and You). “We have drastically failed to provide a safe environment to our girls. In many cases the ‘protectors’ themselves turn perpetrators.” This sort of rape often continues unchallenged. Very often since the victims are younger girls, they are unable to articulate what is happening and often even when they do, they are disbelieved. All of this adds to their trauma. The problem is made worse by the lack of structural support systems like creches for working mothers who live in slums. “When they go out to work, who are they supposed to leave their children with other than neighbours and relatives?” asks Swati Maliwal. In fact, fear of crime keeps women in outer Delhi at home where they can keep an eye on their children, I found while researching this 2018 story on women and work. A shameful silence  A still from Mira Nair's Monsoon Wedding Meera Nair’s 2001 film, Monsoon Wedding brought sexual abuse by family members out into mainstream discussion. Unfortunately, it has been an outlier. The December 2012 gang-rape in Delhi reinforced the idea of unsafe public spaces and stranger rape. In policy terms this was reflected with a growing emphasis on better street lighting and CCTV cameras. All this is welcome. Yet, despite the data, child sexual abuse by family members is something we still don’t talk enough about. “There is a complete lack of awareness. It is not in people’s psyche,” says Maliwal. When she spoke up against her own child sexual abuse by her father in March this year, Maliwal says she was ruthlessly trolled. “All kinds of statements were made that I was putting ‘dirty’ ideas in people’s minds,” she says. But along with the abuse, she also received hundreds of calls from girls and women who were reaching out to share similar stories, she says. Way forward  Source: Arpita Biswas/Feminism in India “In the absence of accommodation and food, the biggest challenge arises when a close family member is involved,” says Delhi-based child rights lawyer, Anant Kumar Asthana. The only option, he adds, is a government or NGO-run child care institution. There is also a “lack of quality support persons”, continues Asthana and there is need for “substantial improvement in order to be of actual benefit to victims”. What happens on the ground is that “victims lose all existing support [from the family] and hence require speedy financial assistance that is needed to restore agency and dignity of life,” he says. Maliwal adds: “What we need is a massive awareness campaign.” In incest cases a robust rehabilitation policy is needed to enable the mother to take a stand. “There is a lot of taboo and stigma and people don’t want to talk about it but it’s high time we broke the silence.” If you have a complaint or would just like to speak to someone please call:

Childline: 1098

Central police helpline: 112

Helpline: 181

|